27 de enero 2022

Dialogue and Elections: “The Peaceful Way Out of the Dictatorship”

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Importers describe the corruption in customs step by step: extortion of businessmen with millionaire charges, while “friends” are “untouchable”

At the end of the first semester of 2021, 'Raphael', manager of a company that imports food products and distributes them in Nicaragua, received a notification from the General Revenue Directorate (DGI), informing him that they had ordered an audit of his company.

Shortly thereafter, while they were looking for a way to resolve this technical issue, the Directorate General of Customs Services (DGA) informed them that the amount they were reporting for freight on the imported merchandise was too low, and stopped customs clearance to review the entire process.

Four months later, as the imported food was approaching its expiration date, and the Christmas shopping season was looming ever closer on the horizon, the company 'Raphael' works for was forced to pay approximately $300,000 to recover its merchandise, and start distributing it just in time to stock its customers' shelves.

‘Raphael’ doesn't seem too sorry that he had to shell out almost a third of a million dollars to pay his extortionists. On the contrary, he had three reasons to feel relatively at ease.

The first is because they were able to get their goods out and sell them on time. The second is because the real overcharge he had to pay was close to US$80,000. The third is because they were asking for almost $600,000 to ‘solve’ the problem, so he was able to ‘save’ more than half of it.

Questioning to whom the money was left, ‘Raphael’ thinks the answer is varied. The amount paid to the DGA, after reaching an agreement with them as the official agency, “was left to the State, but the ‘overcharge’ was left to some people... middle and high level officials, whom I don't know”, he assures in an anticipatory tone.

His story is by no means exceptional. CONFIDENCIAL spoke with a dozen sources, including importers and exporters, managers, customs businessmen, former union leaders and experts on the subject, who describe a system that rewards allies of Daniel Ortega's regime and punishes outsiders, while fraudulently raising the amounts that the State can collect, and the bribes that employees can pocket.

Sources with more experience in the customs sector, who have seen how the system began gradually but steadily degrading starting in 2007, and how that process began accelerating in 2018, point to two people as the ringleaders of the irregular scheme that has become ingrained in Nicaraguan customs: the director of Managua Customs, and his right-hand man.

Óscar Moncada Lau, who is in charge of Managua Customs, is also the brother of the presidential couple's security advisor, sanctioned by the United States, Néstor Moncada Lau, who in turn controls the General Revenue Directorate, the National Police and the Ministry of the Interior.

“The one in charge of Managua Customs is Oscar, who runs that agency as if it were an independent entity, because he knows he is backed by his brother Nestor Moncada Lau - security advisor to the presidential couple, who also controls the General Revenue Directorate, the National Police and the Ministry of the Interior”, says 'Arturo', a lawyer who has seen the way in which the administration has been perverting the system.

Oscar Moncada Lau’s second in command is Carlos Baltodano, a customs professional with a lot of experience and knowledge of the specialty, who previously worked in the Technical Directorate of the Central Customs, and then in Valuation, but “now he imposes values, changes procedures, moves away from legal principles and tariff classification, to collect more taxes”, says ‘Arturo’.

“His classic response is ‘this is the way it's done here. Go complain wherever you want, because that's the way it's going to be done.’ However, imports from ‘friends’ are ‘untouchable’. In those cases, there is no doubt of value, and deliveries are immediate. They make their declaration, and their merchandise leaves in an hour, as you demonstrated when you denounced the illicit scheme that operates in the Eastern Market,” the expert recalled.

According to the current law, complaints, claims, appeals, appeals and so on can be resolved in the higher instances of the Nicaraguan customs administration, and then, in the Customs and Administrative Tax Court (TATA), which until a few years ago could be expected to act according to law, sources say.

By definition, the TATA is an autonomous and specialized entity, independent of the customs service and the tax administration. It is authorized to hear and resolve all cases in customs and tax matters in the last instance, through administrative channels. Its resolutions exhaust the administrative process, although they may be appealed by means of appeals for protection or administrative litigation.

In practice, for some years now, “both the TATA and the customs administration have been acting out of voracity for tax collection. It seems that they are oriented to rule in favor of the claimant when the amounts do not exceed 5,000 dollars, but above that amount, it is impossible to win a case”, says Arturo.

Citizens wait to complete import and export procedures at Customs. // Photo: Confidencial

‘Gerardo’, a high-level executive of a customs company, assures that “Customs uses different figures to charge more. If the declared value is $20,000, they say that in their database it appears that it is $30,000, and on that basis they calculate taxes.”

His perception is that this became more acute in 2018, because as of that year, it became more frequent for an importer to have the laws applied to him in a discretionary manner. Businessmen in the sector come to know about these cases, because the aggrieved party appeals to the Chamber of Customs Agents and Warehousemen of Nicaragua (Cadaen), to draw up an appeal and present it to the clearing customs.

Then, when the response is negative, which it almost always is, you can go to the Director General of Customs Services, who almost always ratifies the decision of the customs clearance office, before which, there is still the instance of the TATA, which in most cases, ends up ruling ‘not applicable’.

“Before, when you went to the Tribunal - because your evidence was strong - you won the case, but as of 2018, no matter how strong your evidence is, you will always get negative answers. There is a unity between Customs and the Tribunal, which has already lost its impartiality. We are totally defenceless,” assured ‘Gerardo’, a high-level executive of a customs company.

“When they apply a doubt of value, even if the importer can prove how much he actually paid to his foreign supplier, Customs and the Court reject that evidence, and force you to pay what they say it should be”, fines included, reiterated ‘Gerardo’.

This is what happened to ‘Leonardo’, a businessman who has to import raw materials to keep his business running. He recalls an occasion when his business was affected by one of these undue charges, so they asked for the support of a trade organization associated with the Superior Council of Private Enterprise (Cosep), an entity that helped them to prepare a letter that they sent to the competent authority.

The response was as expected: “‘file an appeal. We presented it, and they answered by asking for a lot of documents about the import process that we did not have at that moment. In the end we ended up paying the value doubt, plus ten additional days of warehousing, floor delay, carrier cost. We paid triple, so from then on, we pay what they ask for, because we learned that you will never beat them.”

Being left alone is, again, one of the reasons why ‘Raphael’, the manager of the company that imports food products, was happy to pay a little less than 300,000 dollars in total, because both DGI and DGA employees who communicated with him had already informed him that he would have to pay them almost 600,000 dollars to recover his merchandise.

“They caused the problem, and then gave us the solution”, he explains, recalling that their dispute with Customs was “relatively small” - in the range of US$20,000 - and ended up being resolved with a payment of US$30,000, “including overcharges”.

That was no big deal, compared to the DGI's claim, which imposed a $200,000 charge on them, which they refused to pay, thinking it was better to fight in court rather than give away all that money.

After making all the appeals, and finding that they could not win because the system had closed ranks against them, the company gave up and decided to pay, but by then, the cost had tripled, and was approaching $600,000, until a manager approached them, and told them that their problem could be solved with $250,000.

“They make it so difficult for you that paying 250,000 dollars is glorious, because they are offering you a salvation that nobody else is going to offer you. We know that of the 250,000 dollars we paid, 50,000 remained in the pockets of some people, not in the institution's accounts, where some 200,000 must have entered”, he said.

After that, the company's relationship with Customs has been “relatively calm. There has been much more openness, in terms of understanding that we need to collaborate, although sometimes there are complications and logistical obstacles that they offer to solve through economic ‘support’”.

A single exception is at odds with the rest of the cases that businessmen shared with CONFIDENCIAL.

‘Fernando’, co-owner of a family business dedicated to the trade of mass consumption products, says that when bringing his merchandise into the country he has never had a doubt of origin applied, nor has he had a product rejected or delayed for any reason, because “we have never overvalued or undervalued merchandise. Before, there were times when we were overcharged, especially during the time of the liberal governments,” he said.

Even so, he recognizes that “the work of Customs can be improved”, and although it makes him lose time, and sometimes part of the merchandise is damaged, he says that he has never paid a bribe.

“I don't know if they ask my customs agent, but he knows I'm not going to pay bribes, so maybe that's why they don't even tell him. Everyone is used to paying more to avoid problems, but I don't like corruption,” he reiterated.

Corruption is an evil that is known and experienced at the offices, where it is decided at what time to yield, how much to pay, and to whom, but there is also a front line where the doubts of value, the repairs, and the demands to pay others are received, either in cash or delivering some bills disguised in a paper, and the people who who are in that line are the managers.

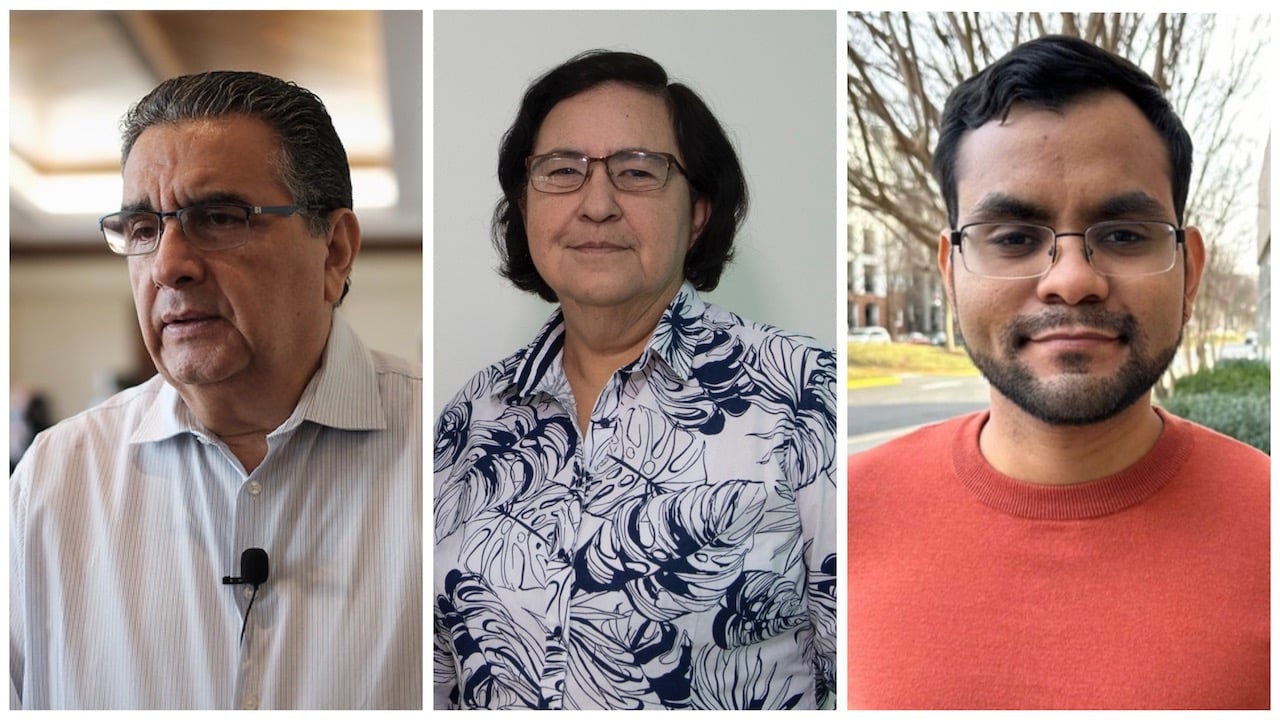

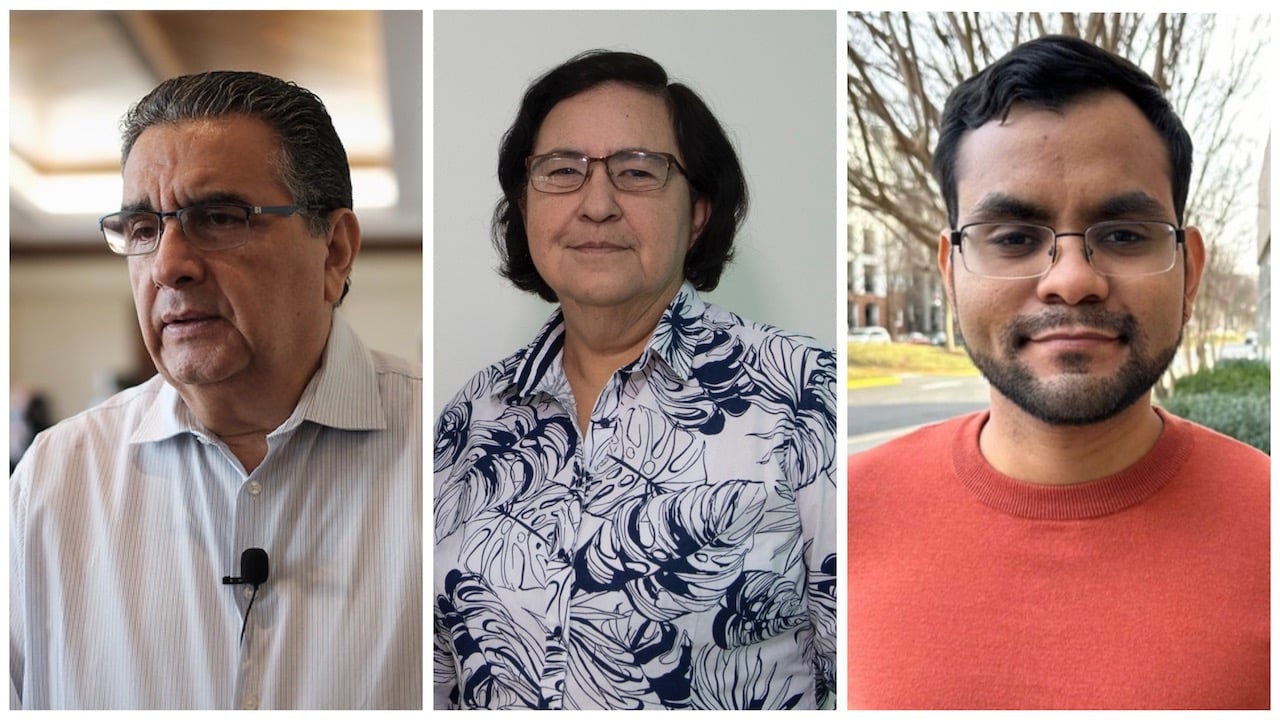

‘Mauricio’, ‘Tony’ and ‘Cesar’ are three of those employees who work for a customs agency and see first-hand how starting from the most basic level of customs personnel - the customs inspectors - to the most senior managers within the system, they all take advantage of the absence of an authority determined to comply with the law, and get richer in the process.

‘Mauricio' came to work in a customs company at a very young age, thanks to the encouragement of a family member. For this reason, he recalls that he was astonished to see that the system was 'oiled' with money “because I had never seen anything like that. Now it seems normal to me, because my colleagues told me that was normal, and I see that everyone always does it that way”.

“There are auditors who ask me, 'Does the client give cash? If I say yes, they solve it immediately, they send the mail to the Technical Department, to make the inspection of the cargo, and instead of taking up to three days to review it, they solve it in half an hour, and proceed to nationalize it. If I say no, they simply delay everything,” he explains.

‘Tony’ has been working in the customs sector for a decade. He says that there was already corruption when he arrived in the system, but “now it is more blatant. Before, there might have been fear that a boss would discover them and sanction them, because they claimed to be different from previous governments, but from 2019 onwards, they ‘let loose’. If the bosses allow it, it is because they are corrupt, and in being so, they are not going to go without their portion,” he reflects.

“To be a customs controller you don't need a degree, you just need to take a course, so any high school graduate can apply for the job,” explains ‘Cesar’. When a van loaded with merchandise crosses the border - sometimes after waiting up to three days to cross - it is assigned to a controller to inspect it, which can mean many hours of paperwork.

Sometimes, the delay is so long, that a cab is paid for the controller to accompany the truck to the company's warehouses, where it is not uncommon that a ‘bonus’ of 1000 córdobas per container awaits him “to oil the procedure, and that he refrains from being very meticulous when reviewing the merchandise as well as the documentation”, he says.

The stories that ‘Tony’ shares are consistent with those told by ‘Cesar’, although with one clarification: “there are importers who want to make everything legal, especially the transnationals; while most of the national ones encourage it, by giving their personnel the green light to pay”.

Some of the latter have an established fee of 1,000 córdobas per container, so that the customs inspector “does not delay checking containers. One time, a gauger received 15,000 cordobas in a week. What I don't know is how the company justifies the expense in its accounting systems,” he admits.

The high-level executive of a customs company, ‘Gerardo’ tries to justify himself by saying that “it is cheaper to pay 3,000 to 5,000 córdobas to a customs broker than for Customs to charge you 30,000 to 40,000 córdobas by imposing an arbitrary decision against its clients”.

‘Alejandro’, a sales executive for a foreign company that exports food products to Nicaragua, observes that Nicaraguan Customs personnel “are marked by the desire to make easy money. They look for any way to charge you whatever it takes, to throw it into their pockets. It's simple corruption. If you don't give them money, but you give them a royalty of your own product, they ‘speed up’ the process and let you pass”, he says.

‘Rubén’, who is in charge of getting his company's cargo through Nicaraguan customs, has a simpler, time-tested method: he makes ‘friends’ with the customs personnel and gives them money - sometimes up to 600 córdobas - “so they can go and have something to eat”, thus saving time and higher payments.

“The existence of illegal charges is already normal. Some people in Customs tell me that they have a list of lawyers who make false powers of attorney, and a ‘red list’ of importers who have tried to cheat Customs. They review any movement they make, so they always delay them, although I do not rule out that they have political reasons to bother them,” argues ‘Mauricio’, a manager.

Nicaraguan customs are very important for the country's fiscal stability, since the 27 001 million córdobas that it plans to collect in 2022 are equivalent to 31.8% of the 84 902 million córdobas of tax revenues that the State foresees for the current year, as reflected in the General Budget of the Republic approved by the National Assembly.

Its importance is such that two business organizations pronounced themselves on the need to review what is happening within the country's customs system.

When consulted by CONFIDENCIAL, the Nicaraguan Association of Plastic Industries (Aniplast) asked that “they should stop affecting us with these doubts of value, because that increases our costs, and makes what the citizens pay more expensive. We need to be given the credibility we deserve, especially because we present international invoices, we pay our taxes... nobody is willing to undervalue merchandise”.

27,001 million córdobas are expected to be collected by Nicaraguan customs in 2022, an amount equivalent to 31.8% of the country's tax revenues estimated in the General Budget of the Republic.

The Chamber of Customs Agents and Warehousemen of Nicaragua (Cadaen) said that they will try to continue to influence during the meetings of the Operational Technical Committee that meets every 15 days, in which land carriers, cargo consolidators, free zones, customs agencies, etc. participate.

In this forum, meeting after meeting, the problems that the administration causes to the companies, both those that manage the cargoes and the owners of those cargoes, are brought to the attention of Customs.

Given that the response is that “they take note, and in some cases give answers, but most of the time they do not”, the Chamber admits that they have failed to escalate to other authorities (such as the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit) that, at least on paper, supervise or have hierarchical supremacy over customs, so that the system operates in accordance with the law, because “everything we raise has a legal basis”.

This article was originally pubkished in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Durante más de veinte años se ha desempeñado en CONFIDENCIAL como periodista de Economía. Antes trabajó en el semanario La Crónica, el diario La Prensa y El Nuevo Diario. Además, ha publicado en el Diario de Hoy, de El Salvador. Ha ganado en dos ocasiones el Premio a la Excelencia en Periodismo Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, en Nicaragua.

PUBLICIDAD 3D