Nicaragua: Public Employees Hindered from Traveling to USA

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Some words for those who live in the United States

In 1986, author Salman Rushdie, best known for his controversial novel The Satanic Verses traveled to war-torn Nicaragua thanks to an invitation from the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers, a group that the author described as an “umbrella organization that brought writers, artists, musicians, craftspeople, dancers and so on, together under the same roof”. From that visit the book The Jaguar Smile was written; a small, but insightful look into the way the Sandinistas were running Nicaragua after 7 years in power. The book was met with criticism for the way Rushdie weaved his clear political bias towards things the Sandinistas were accomplishing, despite the numerous issues that any Nicaraguan—whether they lived in the country at the time or were in exile—knew about.

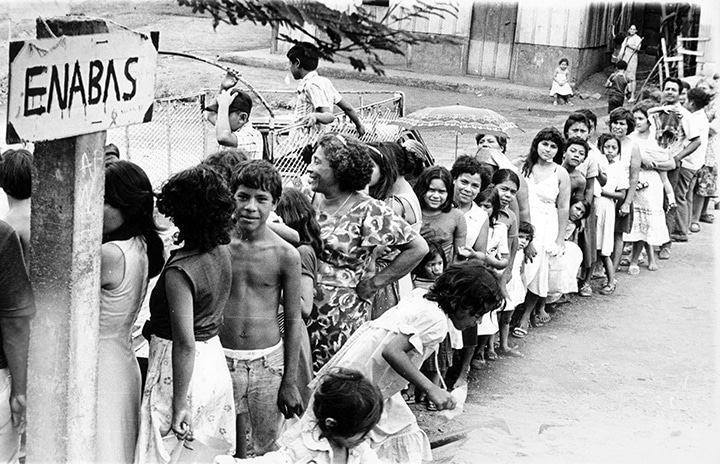

I’ve read the book twice—it’s relatively short. The first time was at age 17, when I found it in my uncle’s home. During that time, I somewhat shared many of the author’s feelings on how the movement and government did certain things. I say “somewhat” because even during that time in my life I could put 2 and 2 together and figure out that the Sandinistas were into some dubious things that were typical of third world revolutionary movements. As I read Rushdie’s words, I understood how he became enamored with the picturesque atmosphere that he saw; it’s clear that he got the grand tour. In the 80s, I didn’t live in Nicaragua but did visit from time to time. I got to see the effects of the economic sanctions, mixed with the revolutionary way of doing things during the tail end of a bitter civil war with the Reagan backed Contras. The Nicaragua of the mid-to-late 80s was one trapped in time compared to neighboring Costa Rica, which was and continues to be the complete opposite—moving forward and never looking back. There was plenty of blame to go around, and the Sandinistas were quick to point fingers towards others but refused to turn them on themselves. The mass exodus of Nicaraguans who exiled to Costa Rica and the United States only fueled the fire that was an economic depression that plunged the country to where is still resides today: the second-poorest nation in the western hemisphere.

The second time I picked up the book—having swiped it from my uncle’s possession, claiming it for myself—was just recently, almost 26 years later. At 43, I am now a writer, chronicling from afar the social-political turmoil that surged back in April 2018 in the form of 3 books and numerous opinion pieces that have been published through Nicaraguan news outlets and online magazines. The “rebelión de abril” or April rebellion marked a new chapter in my poor nation’s often dark history, full of dictators, filibusters, interventions, and wars. During this time, most of the country’s sectors: youth, business, farming, and other social movements had finally grown tired of the corrupt ways of the current government, led by the forever President—Daniel Ortega and his vice president and wife Rosario Murillo. This power scenario is something straight out of House of Cards with a little Macbeth sprinkled on top.

A mix of frequent protests, mass marches, general strikes, and barricades put the brakes on the country as a whole and debilitated the regime to the point where it was widely felt that Ortega was on his way out well before the 2021 elections. But then he went “all in” and began to capture, torture and even ordered to kill all those who stood in his way. He became exactly (many would say worse) who he and his movement sought to overthrow once upon a time—Anastacio Somoza, Dictator of Nicaragua. What has happened in my country can only be described as something inspired by Shakespeare’s tragedy of that Scottish soldier, turned tyrant, who let ambition and greed take control, thus turning him into a monster willing to slaughter anyone who dares go against him and his kingdom.

Today, the Ortega-Murillo regime has a vicious grasp on Nicaragua. They have accumulated over 150 political prisoners, 37 of them rounded up within the last 3 months, 7 of which were poised to be presidential candidates. No one is safe; Ortega has even imprisoned former Sandinista revolutionaries who fought on the front lines, governed beside him during the 80s and even saved him from likely death by orchestrating a swap for his release from Somoza’s torture cells. Today, none of those things matter… if you turn your back or protest against him, you are committing acts of treason against Nicaragua’s sovereignty and thus become subject to capture, trial and prolonged imprisonment for simply using your right to free speech.

So, similar to how things went down back in the 80s, Nicaragua is once again seeing another mass exodus of its citizens, many of whom were once political prisoners—persecuted and harassed daily—while others are folks who simply refuse to live under any more political, social and economic uncertainty. If you ask any of these individuals what they feel about Ortega’s job as president, they will tell you that he isn’t governing, instead he is just wielding his iron fist from the comfort of his home which was confiscated after the fall of Somoza; Ortega seized it for himself—clothes, jewelry, furniture and all—from a man named Jaime Morales Carazo, who decades later would become his vice president, even after years of opposing him and his government.

Nicaragua ’s future is fleeing once again, moving as far away as possible; escaping a dystopian society that only looks to its violent history to resolve its issues and chooses to indoctrinate and control public opinion by bolstering a tailor-made Sandinista past, present and future and by spending on things like parks and entertainment that may look pleasing to some eyes, but don’t help in ways of improving the economic instability that has been hurting the country for decades. They are leaving because Ortega’s corruption is just too rampant to fight against—he has the power and the weaponry of the national police, army, and paramilitaries. Those who are leaving are looking elsewhere because if you are not a Sandinista militant, you are not a true patriot.

I have gotten to know and write about many people who made the conscious decision to stand up and have their voices heard, only to see themselves thrown in prison or forced to leave everything they know behind. Many of them are here in the United States, having sought political asylum, looking to start anew, survive in a completely different world, and still have time to continue in the fight “la lucha”, even from far away.

It’s a rough deal for many of them, but they do their best to pull through. From a couple from Masaya who joined the protests and were then imprisoned just 6 months after getting married, the firefighter from the same city who would run from one barricade to another, avoiding bullets in order to medically help or save injured protestors, the priest who opened his church doors so that first responders could help those in need, the psychologist from Granada or the young woman with cancer from Diriamba, both of whom joined and fought from barricades and the “campesina” or farmer who spent time in a torture room, listening to police tell her that her 2 boys would be murdered while withstanding hits to her temple and feet with rifle muzzles all while her head was covered with a bag.

I could keep on going—I’ve written about so many, but back to my point.

As I read The Jaguar’s Smile for a second time, I constantly asked myself if its author still supported the Sandinista mystic or if he realized that the criticisms outweigh any positive feelings he may have had. Rushdie called out the Reagan administration for their “dirty tricks” and even quoted Ortega as saying that the American government was “worse than Hitler”. I wondered if Rushdie had seen how Ortega has been behaving since 2018; would he consider throwing Ortega’s quote right back at him? Then I read Rushdie’s piece titled Nicaragua's Tragedy, coincidently posted while I was typing this article. In it, he talks about how he once believed that the United States was the biggest threat to Nicaragua but realizes that it has always been the enemies within—Ortega and Murillo—the “no-holds barred fascist dictators” as he puts them.

I, too, saw things through a personal and even bias lens when I moved to Nicaragua in the 90s. I lived, matured and graduated from college there and yes… I became enamored with the romanticism. But contrary to many, I was never blinded by it. I saw how—even while not in power—Ortega pulled the strings of chaos during the entire decade of the 90s, leading up to his eventual return to power in 2006. For me, it’s hard to be far away and witness all the wrong that is being inflicted on my country (regardless of not being born there nor living there currently, Nicaragua is still my country). It’s even harder to see how many of Nicaraguan descent, born in the United States, know about what is going on, but since their connection to the country is minimal or tourist at best, their level of “protest” is based on likes on social media posts. That’s fine, no one is expecting them to lobby or give online support for the passage of legislation such as the “Renacer” act or anything of that nature. Besides, if they publicly did such a thing, that would be considered an infringement of the law in Ortega’s Nicaragua—the wording in article 2 of the nation’s “Cyber Crimes” law roughly states that committing such a crime—even from afar—still applies. It’s a joke of a law.

But most of all, it’s hard to see how some American politicians have either looked the other way or barely come out to denounce what is going on. Even worse are the ultra-left in this country who support the regime, repeating everything that Ortega and Murillo constantly spew while standing on street corners with the red and black FSLN flag and posters in support of the regime shouting: “Hands off Nicaragua” as if they know what real repression feels like or where Nicaragua even is on a map.

If you ever get around to reading The Jaguar Smile (you should—reading different perspectives is important) you’ll notice that Salman Rushdie doesn’t necessarily end it on a positive note. He has a conversation with a woman while leaving the country. In it, the woman clearly isn’t happy with the way things are going and doesn’t support the revolution like she once did. That conversation was 35 years ago… Today, things are worse, and many would probably confess those same feelings about similar issues. So, that saying of “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” sure fits well with Nicaragua today.

Nestor Cedeno is a teacher and author. He has written 3 books in Spanish on the social uprising that began in Abril 2018 in Nicaragua: http://nestorcedenoautor.wordpress.com/libro as well as multiple op-ed pieces, published through various Nicaraguan outlets.

Sources

Rushdie, Salman. “Nicaragua's Tragedy.” Salman's Sea of Stories, Salman's Sea of Stories, 21 Sept. 2021, salmanrushdie.substack.com/p/nicaraguas-tragedy.

“Ley Especial De Ciberdelitos.” Ley Especial De Ciberdelitos, La Asamblea Nacional De La Republica De Nicaragua, 30 Oct. 2020, legislacion.asamblea.gob.ni/normaweb.nsf/($All)/803E7C7FBCF44D7706258611007C6D87?OpenDocument.

LEY No. 1042, aprobada el 27 de octubre de 2020

Rushdie, Salman. “The Jaguar Smile.” Kirkus Reviews, Viking, 1 Mar. 1987, www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/salman-rushdie/jaguar-smile/.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D