Dialogue and Elections: “The Peaceful Way Out of the Dictatorship”

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

We dive into the stories of three Ukrainian women with disabilities on pregnancy, maternity leave, and raising children in Ukraine

Olena Akopyan speaks to her children, twins Yehor and Maryana. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / hromadske

Everyone has the right to be a mother or a father, according to Ukraine’s family laws. But problems can arise when people with disabilities try to exercise their rights. Mostly, this concerns discrimination from doctors, the unfriendly architecture of hospitals, and societal stereotypes – such as assumed risks that women would give birth to an unhealthy child and then not be able to care for or raise them.

Similar problems exist in many post-Soviet countries, where people with disabilities usually find it difficult to fit into the wider society. For example, in 2015 in Belarus, child protection services tried to take away a disabled couple’s child. It took the entire country to defend the parents’ rights.

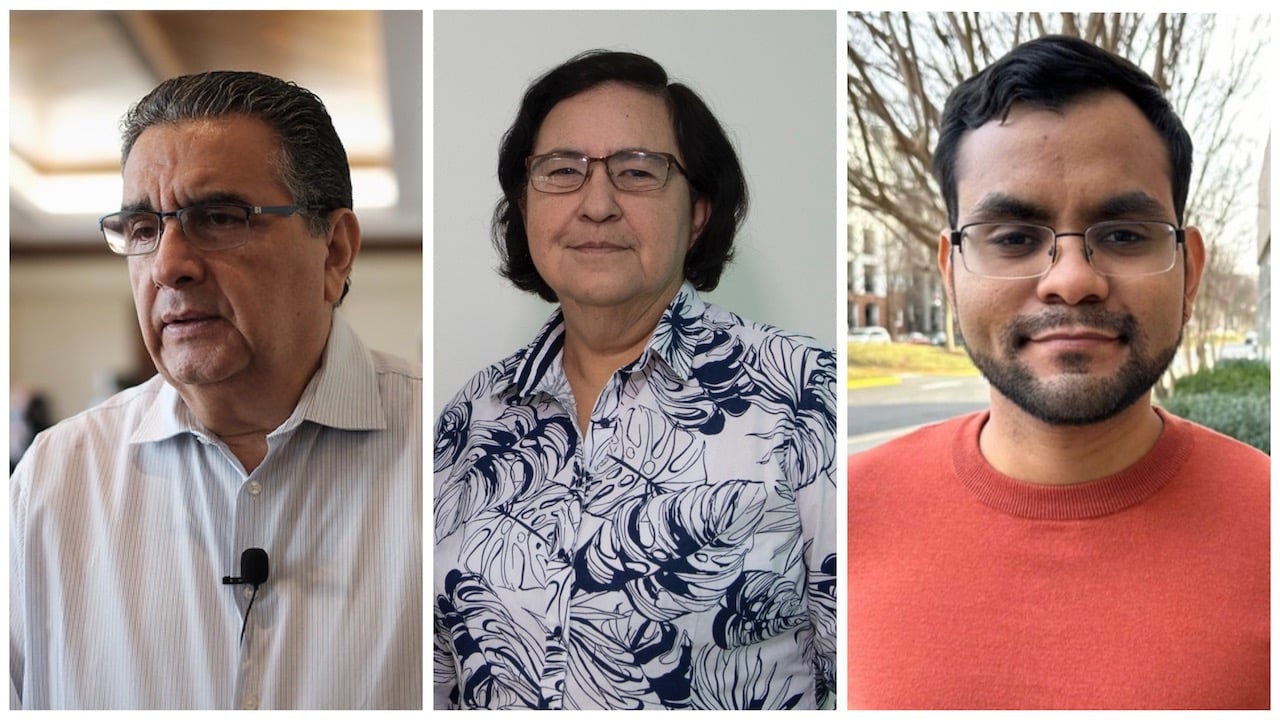

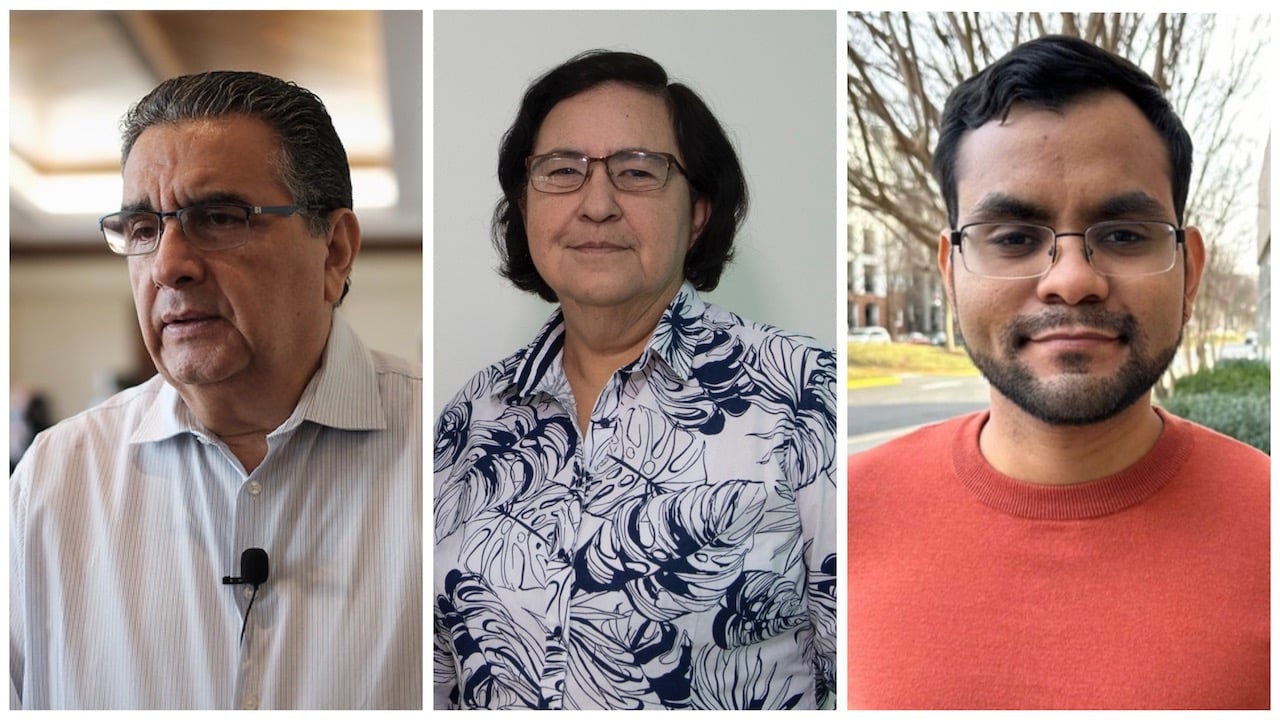

Today, we are diving into the stories of three Ukrainian women with disabilities: Yuliya Resenchuk, who is currently pregnant; Yuliya Akritova, who’s raising her three-year-old daughter Dasha; and Olena Akopyan, mother of two twins – Yehor and Maryana.

Yuliya Resenchuk received spinal damage as a result of a car accident. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / hromadske

“Can I talk about it now?” says Yuliya, speaking excitedly and a little flustered while she looks for her husband’s eyes. “A boy. We’ll have a boy.”

“The doctor showed us each finger and explained everything in detail. It seems to me that he’s preparing us for something with the help of these long descriptions. But no, he says that the child is alright, he’s developing as he should be for the fifth month of pregnancy,” explains Vadym, Yuliya’s husband, with a smile.

The couple is standing in a corridor at the Institute of Pediatrics, Obstetrics, and Gynecology. They just received news of their child’s sex from their doctor.

The couple file into a narrow elevator: first Yuliya in a wheelchair, with Vadym following. They head down two flights, into the Natal Pathology and Birthing department, where they have an appointment with a different doctor. That one prescribes pills that would heighten Yuliya’s iron levels, and once more confirms: their child is developing normally.

This is the couple’s second pregnancy. The first one ended in a miscarriage.

Yuliya and Vadym have been together for ten years. Vadym works a lot, often traveling. After Yuliya ended up in an accident at 23 and received spinal trauma, she’s been busy with social activities – she created a charitable fund and joined a movement to create IT courses for people with disabilities.

The couple has been attempting to have children for the last three years. They’ve gone through numerous tests, received treatment, consulted with doctors. Yuliya would sometimes look after her little nephews, in order to better understand what it’s like to deal with children in a wheelchair.

Six years ago, returning from holidays, Yuliya and Vadym visited a private clinic in order to understand why they couldn’t seem to get pregnant. But it turned out that they were already on their way.

The couple stayed with that clinic.

At the time, I wasn’t looking at any options that involved tests at government hospitals, where they could have told me to get an abortion because I wouldn’t be able to give birth, or that the child wouldn’t be healthy. I didn’t even want to hear that sort of thing, even though I know a lot of these sorts of stories,” says Yuliya.

She was happy with her choice of a private clinic. It was just the doctor, she recalls, who wasn’t attentive. During their first ultrasound on the seventh week of pregnancy, the doctor wasn’t sure whether the child’s heart was beating but told the couple not to worry.

A month after that, on Vadym’s birthday, Yuliya suddenly felt ill and began bleeding. “I scheduled myself for a doctor’s visit and went to the clinic. And I miscarried right on the toilet. They examined me there, wrapped me up, and took me to the corridor to wait for an ambulance.”

When the ambulance arrived, Yuliya lost consciousness. She says she doesn’t remember anything else.

Yuliya worked with a psychologist for the next few months.

“For a woman to lose a child that she was waiting so much for – it is a huge blow. But thanks to the support, I understood that I want a child. And that we’d try again.”

This time, says Yuliya, they approached pregnancy with complete responsibility. They went through tests and consulted with several specialists before conception.

“The first doctor that we went to looked at our tests and analyses and said that we won’t be able to do it, and we can forget about pregnancy. Maybe only via IVF (in-vitro fertilization – ed.), but we hadn’t considered that option. I felt that this doctor just didn’t want to work with us, because it was a difficult situation. We had “peculiarities”, as people love to say here. But the only peculiarity we had was that I could only give birth via c-section,” Yuliya tells us.

Yuliya and Vadym turned to a different doctor, who said that there were no negative signs against pregnancy.

This spring, Yuliya got pregnant for the second time. “This time we’re being taken care of at a government institution. They don’t always have ramps, and I have to enter via the service entrance. But the doctor is experienced,” she says.

Yuliya has been working remotely since the start of her pregnancy. Every day brings greater pain to her back, and prior to this, she suffered from toxicosis for three months.

Yuliya and Vadym haven’t yet set up a room for their soon-to-be baby boy, despite knowing where the bed is going to sit, where the changing table is going to be, and where, eventually, they’ll set up a writing table.

Yuliya Akritova has cerebral palsy from childhood. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / hromadske

“This happened not long ago, two months back. We were eating in the kitchen, and Dasha says to me: ‘Mama, can you walk normally?’ ‘Normally? What does that mean?’ I asked her. ‘Well, like this:’ Dasha got up and walked along the corridor. ‘No, I can’t,’ I told her. ‘Ah, okay,’ and we continued eating. To be honest, I was expecting to hear something like this from my own child a little later.”

Yuliya is sitting on the floor, stretching her legs. Her red-haired, three-year-old daughter runs around her in the bright and spacious room.

“My pregnancy was really easy. But then it got hard. And my stitches following the c-section hurt, and it was hard psychologically. I was anxious, I wanted to leave. But this wasn’t at all tied to my disability. Any woman can go through this.”

Yuliya has had cerebral palsy from childhood. She hasn’t walked since birth, and her mother pushed her around in a baby carriage until a wheel fell off.

“My mother began to teach me to walk by hand. It was difficult – my coordination was damaged, and so I would constantly be turned the other way,” she tells us.

Thanks to this rehabilitation, Yuliya could attend school. But they didn’t want to take her in at first, saying that she wouldn’t be able to handle the school’s program. But her mother insisted.

“I was surprised by the cruelty of the children. And the teachers didn’t understand that I would write slower, not matching everyone’s pace, and so they gave me low grades.”

Starting from the eighth grade, Yuliya changed her attitude towards her disability and stopped being ashamed of it, learned to defend herself, and as a result, her classmates stopped teasing her.

After finishing school, she enrolled in a university specializing in linguistics, found work, and married a man who also had cerebral palsy.

“There was a person who once told me, ‘I feel bad for you because you won’t ever have children and a family.’ This was shocking and offensive. What did it mean: that I wouldn’t have children?”

Yuliya got pregnant after getting married. Gynecologists, during her first visit, asked whether she was preparing to get an abortion. A confused and shocked Yuliya answered “No”, and went to get an ultrasound. She worked throughout her pregnancy, teaching English and German. A day before she was due to give birth, on a Saturday she remembers, she also had lessons. And on Monday, she had a little girl, Dasha. For the first few days in the maternity ward, they wouldn’t give her her child, because she couldn’t stand due to her c-section stitches.

Her husband, Kostiantyn, helped her take care of her daughter for four months, but then he had to leave for work, and she had to figure things out on her own: “She was so small, and my hands shook. I was scared to carry her. I thought that I would fall. I didn’t know how to set her down, how to pick her up, in order to not crush her. She was somewhat soft.”

With time, Yuliya got used to things and figured others out: sitting on the edge of the couch, she would take Dasha from her crib and crawl alongside her. When they needed to go on walks, she would dress her daughter in bed, taking the baby carriage with her and immediately placing her in it – to avoid having to carry her through the whole apartment and risk dropping her. She would bathe Yuliya only with her husband present.

When Dasha got a little older, at the age where she should start walking, her parents bought her a baby walker, since Yuliya couldn’t walk constantly bent over and simultaneously hold her daughter under her arm.

“They told us that baby walkers were harmful to children, that they’ll lose something. Maybe that’s true. But I needed my child to be able to move through the apartment,” she recalls.’

Things seemed to get easier after the first year. They began to go outside more often to the playground. But she still can’t leave her neighborhood with her daughter: it’s hard for Yuliya to get onto public transport, because drivers of trolleybuses and buses often don’t stop directly on the stops, and act as if they can’t see a person with disabilities, while getting on the metro always requires asking for help from the station attendants, in order to get down the escalator.

“I’m scared of getting into the metro with Dasha. Even when we’re heading down via the elevator, the doors open directly onto the yellow line on the platform, and my head begins to spin. I can’t be so close to the rails. And Dasha is very fast, she doesn’t look out for things, she’s not afraid of anything.”

Dasha is the fastest kid at her local playground. In an instant, she’s on the other side of the playground. Yuliya says that the girl is growing up by herself. Dasha helps and is considerate of her mother, knowing what street is better to take, where there aren’t curbs, and where it’ll be easier for Yuliya to step down.

“Once, I was lying in my room and I hear some sort of commotion in the kitchen. Dasha had gotten peaches from the fridge, washed them, and brought them to us. I think that she’s growing up this way because I didn’t nanny her. That is, I couldn’t always hold her in my arms like other mothers do. Not because I didn’t want to – it was physically difficult for me.”

Yuliya plans to go back to work in a few months, while Dasha will head off to kindergarten. Meanwhile, Yuliya is taking driving lessons, in order to be able to take her family beyond the borders of her neighborhood, instead of being bounded by her disability.

Olena Akopyan suffered damage to her spine as a result of a knife assault. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / hromadske

“I saw how some athletes, my opponents, had children, but they couldn’t pay any attention to them. They were constantly at competitions or meets. I didn’t want my children to grow up the same way.”

Olena Akopyan gave birth to twins, Yehor and Maryana, at 41. She’d finished her athletic career two years earlier, at 39.

She never thought that she would be an athlete. She didn’t have the best swimming times at school. “I was constantly drowning,” she jokes.

After ninth grade, Olena enrolled in a conservatory in Bilhorod, a town in southern Ukraine, on the fortepiano course. Once, after returning from her native Yenakiyeve in eastern Ukraine, she was attacked by a man with a knife while walking on the street at night. Operations followed them, wheelchairs, and a medical prognosis that she would regain the ability to walk in a decade. But that never came to pass.

After the assault, Olena finished the conservatory remotely, and then enrolled at the Dnipropetrovsk State Institute of Physical Culture and Sports, and began her professional career as a Paralympic athlete: athletics, cross-country skiing, biathlon, swimming. She’s won 15 prize medals over her career, at Paralympic games in Atlanta, Sydney, Athens, Beijing, and Nagano.

“I wanted a family, but I couldn’t just quit sports, and I was always waiting for a prince on a white horse. When one appeared, I decided to have children,” she explains.

She and her husband went through tests and treatments, after which Olena fell pregnant. She didn’t have health problems for the entire nine months of her pregnancy, and she carefully followed her doctor’s instructions: “My gynecologist set me up to feel that everything was going to be alright. Only after I gave birth did he tell me that I actually had a lot of trouble. But I didn’t know this.”

Until her children were six, Olena raised her children along with her husband. But then they divorced. She says that it only became more difficult psychologically because she managed with everything else – she planned time down to the minutes, in order to keep up with two children, and asked for help from her own mother.

Only then did Olena tell Yehor and Maryana about her disability. She showed them a clip of a reconstruction of the attack on her.

“I explained it to them when they asked themselves. They understood how difficult and scary it was. Sometimes I ask them what they tell the other children if they’re made fun of because of the fact that their mother has disabilities. Yehor tells his friends that his mom is amazing.”

The children go to kindergarten not far from their home. The school specially put their group in a classroom on the ground floor, just for Olena, and did not switch to the first as usual.

When it came time to send the kids off to school, Olena visited several local institutions. Three of them told her that she would be “uncomfortable” there. At the fourth, a gymnasium, they recognized her, her children passed their exams, and they were enrolled. Now she takes her children there with neighbors whose children also go to the same school.

And for extracurriculars, she takes her children to a variety of places: her daughter sings, dances and her son goes to a Lego studio. They learn English together and practice swimming under Olena’s guidance. Yehor has already won his first gold medal at swim meets and says that he’s going to be a champion, just like his mom.

“When we were at training, a boy with cerebral palsy showed up. Yehor jumped over to him and showed him how to swim. By playing, he proved that you can swim and not be afraid of anything. And so my children even help my work.”

But they’ve begun doing more things together as her children grow older: cleaning, cooking, walking around town, traveling around Ukraine, and traveling across the border.

“My daughter helps out a lot. Maryana once cooked breakfast by herself. Yehor constantly puts away and retrieves my wheelchair from the trunk of our car, and recently fixed the window. Sometimes I get scared that I won’t be able to do anything myself and that I’ll need some sort of help. But once we were heading to Mezhyhirya Park and took our neighbor with us. She was so grateful and said that she would not have been able to get there by herself.”

Olena admits it's important to have a goal before your eyes to strive for. At one point, an example of this was her friend Svitlana, who also used a wheelchair. Svitlana Trifonova, also a Paralympic athlete, participated in the Moscow-Kyiv-Kryviy Rih marathon in 1991. She had two children but continued her athletic career.

“Now this picture might fade away, because I built a successful career for myself, had children. I have everything I wanted. But then I remember that my children are only in fourth grade, and we still have so much to do!”

This article was published with the authorization of Hromadske International.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D