30 de noviembre 2021

The Return of the Military

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

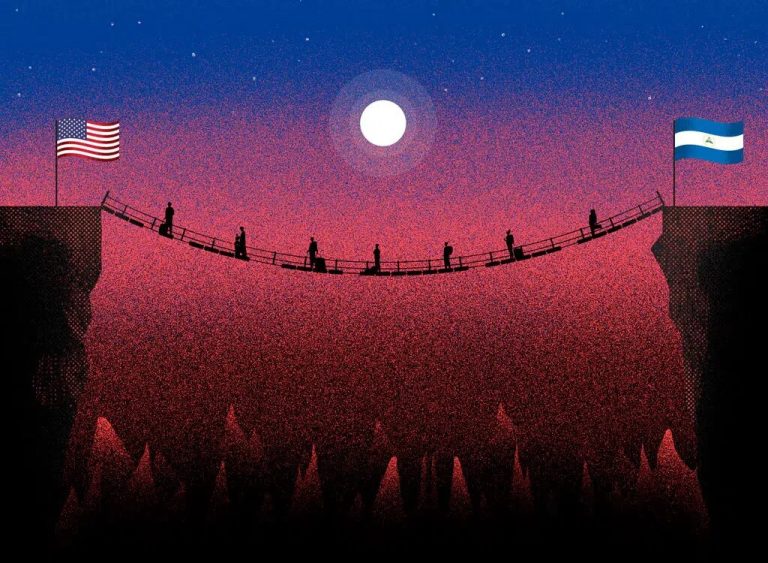

A former state worker, three victims of repression and a university student fled poverty, persecution and hopelessness in Nicaragua

The day “Carlos” left his home in Ciudad Dario, Matagalpa, he felt ready for the long journey to his final destination: the United States. He knew it would not be easy to cross irregularly, but it was the only way and he was determined. He soon learned that there is no way to be prepared for feeling that he could die inside a container in which he was traveling with dozens of people, all trying to breathe through a tiny hole, all fearing asphyxiation.

That was just one of several anguishes that this 42-year-old man survived. Unimaginable anguish, one also experienced by “Andres”, 29 years old; the sisters Sofía, 17 years old; and Camila Quezada, 18 years old; and Meyling Cruz, 22 years old, Nicaraguans who also shared their testimonies with CONFIDENCIAL. Between January and October 2021, the United States recorded more than 58 000 apprehensions of Nicaraguan migrants who entered that country irregularly and who also risked undertaking that dangerous and uncertain journey.

What he experienced on his journey to the United States he had only seen in movies and series. “Those 28 days were the saddest. I never thought… I can’t fool you. Nobody told me that they were going to put me in a container with a single hole through which air enters, that you feel that you are drowning, that you despair... these are horrible things,” says ‘Carlos’ on the phone from Florida, where this Nicaraguan refugee applicant now lives and asks for his identity to be protected.

‘Carlos’ is an engineer, originally from Ciudad Darío, the place from which he parted on July 29 this year. He worked for a state institution for many years, and was also part of the party structure of the ruling FSLN. He says that the 350 dollars a month he earned was not enough to provide for his family, made up of his wife and three children. He never thought of emigrating, but when his daughter told him that she hoped one day they would be able to have their own house, he felt like crying and decided that he should go to the United States, where a niece would be waiting for him and give him a place to live.

He agreed to pay a “coyote” or “pollero” $3800 and set out on the journey with a group of 120 people, which included mainly young men, but also entire families with small children. “They came from Chinandega, Managua, León, Ciudad Darío, Matagalpa, Sébaco, La Trinidad, Estelí, Bluefields and Nueva Guinea,” he recalls.

The trip from Nicaragua to Guatemala was calm, “like an excursion” of three buses that always traveled together he says, but that changed once they arrived in Guatemala City, from where they began to move irregularly. “There they told us to hide our ID cards, money, and all our belongings, because we were moving like a sack of drugs from there on, like a packet of cocaine, already hidden in a car,” he explains.

From that moment on, “Carlos” felt dehumanized. “Like cattle”, “like an inert lump” that must go unnoticed by the immigration authorities, police and military, who in some cases let them pass in exchange for payment from the “polleros” who organize the route throughout Mexico. When they were intercepted by drug cartel members, they had to give them a “password” to get through: “We are from ‘Reyes’ group,” they had to say. If “Reyes” had paid the “toll”, then they could continue.

“Carlos” recalls the fear he felt when he heard screams and a shooting a few blocks from where he was hiding in Tapachula. Shortly after, he was told that another group of migrants had been attacked by drug traffickers, supposedly for not paying the “toll”. He assures that it was during that incident that a migrant from La Trinidad, Estelí, died last August, outside a Mexican shelter in that city.

They traveled at night, on sidewalks and crammed into trucks, vans and cars, stopping in precarious hotels, chicken coops or ranches with warehouses where they were locked together with other groups of migrants during the day, using pieces of cardboard to avoid sleeping on the wet ground, sometimes without food for long periods, guarded by men with heavy weapons.

He remembers the constant cries of children, women and men, because of hunger, the cold, the shame of having to relieve themselves in front of everyone during the trip, because of the danger.

“Carlos” turned himself in to the authorities on August 23. Before that he had to cross the Rio Bravo, where he affirms that he saved a girl who was about to drown amidst the chaos of the migrants being thrown into the water from the boats in which they had been transported by young men paid by the “polleros”.

In the company of six other people, he walked and walked, turned on his cell phone and with the help of a map managed to locate himself to continue moving forward until he finally saw a U.S. border patrol to surrender to. “When we got there, we cried. You know, making the investment in that trip. I started to cry when they put me in jail, they put me in the famous “hielera” or “cooler”, they threw some thermal blankets for us to sleep on the floor,” he recalls, referring to an extremely cold room in which they put the apprehended migrants inside the detention center at the U.S. border.

The “hieleras”, like the one described by “Carlos”, are the extremely cold cells in which migrants are locked upon arrival at U.S. border detention centers. Photo: taken from a report by Human Rights Watch

He left the center two days later, after an interview with immigration authorities. Today he works washing dishes in a restaurant and when he recalls that trip he repeats that he would not recommend it to anyone. “It’s horrible, I thought I was going to die. I'm telling you I did,” he admits, recalling those moments inside the container. “Carlos” says that thousands of others like him have left his department, he knows this because the FSLN party structures keep a count of recent migration, he assures.

Driven out by poverty, political persecution and hopelessness, more and more Nicaraguans have left the country in the last year for the United States.

More than three years have passed since a serious socio-political and economic crisis erupted in Nicaragua, a product of the lethal repression and police state imposed by Daniel Ortega's regime since 2018. Since then tens of thousands of Nicaraguans have left mainly to Costa Rica, the United States and Spain. The UN refugee agency, UNHCR, reports that more than 110 000 Nicaraguans have been displaced in search of refuge since then.

The more the crisis worsens, the more Nicaraguans immigrate, and the flow to the United States has grown considerably. This is evidenced by figures from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP): if in 2017 there were barely 1,000 apprehensions of Nicaraguans at the U.S. borders when trying to enter the country irregularly, by the end of fiscal year 2021 (in September) there were more than 50,000.

Most of the arrests of Nicaraguans this year occurred between June and September, when, in the run-up to the November elections, the regime unleashed a new wave of repression, which included the hunt for opposition presidential aspirants, civic leaders, businessmen, former diplomats, journalists and human rights defenders. A considerable flow continued in October of this year, with 9256 new arrests of people of Nicaraguan origin.

On November 7, the regime declared itself the winner of elections without political competition, without the participation of more than 80% of the citizenry - according to the independent observatory Urnas Abiertas - and without the recognition of more than 40 countries, which instead reject the authoritarian drift of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo.

Given this scenario and the high uncertainty about the country's political and economic future, Nicaraguan migration to the United States will continue, warn migration experts. “Because migration begets migration, once this wave of migrants settles, they will call their relatives and Nicaragua will join the countries of northern Central America as a recurrent sender of migrants to the United States,” projects researcher José Luis Rocha, in his essay “Three years of repression and exile of Nicaraguans: 2018-2021”.

When “Andres” gave this interview he was in Tapachula, Mexico, and said he would try, for the second time, to reach the U.S. border to seek asylum.

The 29-year-old artist left Managua last June, after witnessing with terror the hunt unleashed by the Ortega-Murillo regime on civic leaders, former diplomats, human rights defenders, journalists and bussinessmen.

“Andres” feared that they would also come for him, as he had been warned on more than one occasion by police and Sandinista sympathizers in his neighborhood. The lyrics of his urban music against the Ortega Murillo regime were the reason for the political persecution against him. “A policeman told me that he was going to make me disappear if I didn’t shut up, that the music I was making was moving people and that it was hurting them, that it was inciting people against the government,” said the young man, who asked that his identity be protected, as he fears reprisals against his family in Nicaragua.

“Andres” left with a group of friends and acquaintances. There were six of them who set out on their own, then joined together with more migrants along the way, until they reached the border between Guatemala and Mexico.

Once there, they learned that crossing Mexico without the approval of “coyotes” or “polleros” was almost impossible. That “approval” cost him $2,000. “If you want to go alone you won’t get very far, you can’t. I've heard of people who were kidnapped. I heard of people who were kidnapped, of women who were gang raped. You have to negotiate with them (the “coyotes” or “polleros”), they talk to their bosses so they don’t do anything to you. Usually, the polleros work in coordination with members of the drug cartels and, in exchange for money, the migrants receive the “passwords” they must use to be allowed to pass”, he said.

From Chiapas he went to Puebla, then to Guadalajara, Mazatlan, Hermosillo, until he reached Rio Colorado. It was a 17-day trip, plus a forced month-long stay in a town near the border, because a migrant in his group became seriously ill. “You are battling against Migration, the police, the cartels, battling against covid. It seems that it hit us (all of us), a friend of mine was hit hard and we had to wait for it to pass,” he recalled.

The young man turned himself in to the U.S. authorities on September 15. He spent three days in a migrant detention center in Yuma, Arizona. He tried, unsuccessfully, to explain his situation to the agents, why he needed to apply for asylum, but they would not listen to him.

The route that “Andres” followed the first time he made the journey to the U.S. border to seek asylum. Photo: Capture from Google Maps

The trip had been in vain. “Andres” was returned to Mexico in a plane that landed in the south of the country, near the border with Guatemala, in Tabasco. “I can't stay in Mexico, I would prefer to return to Nicaragua, but I don't plan to go back either, because the situation is worse. I prefer to keep trying. I am going to try through Monterrey, to re-enter the United States so they will listen to me,” he said.

During his journey, “Andres” met many Nicaraguans, “entire families, some victims of police repression, I also met a Sandinista worker, from the Ministry of Health, I have met single women with children”, he said. All trying to get to the United States, all with the fear and uncertainty of whether they would make it.

Finally, 50 days after giving this interview, “Andres” arrived in the United States on November 23rd. “Yes, I made it, they released me just now,” he wrote in a brief text message.

Sofia Quezada recently turned 18. She says she never thought she would reach adulthood in an unknown country, leaving behind the life she knew and the plans she had in the department of Leon, where she is from.

Her parents put together the more than $7,000 that a “coyote” was charging, and, in the hope that everything would go well, they chose to assume the great risks of the irregular journey that their only two daughters, Sofia, 17, and Camila, 18, had to undertake to get to the United States. It was better to take the risk than for them to continue living in Nicaragua.

Both girls had been victims of the National Police. Camila, during the citizen rebellion against the regime in 2018, was arbitrarily detained and beaten by police officers after being arrested for pasting ballots with anti-government messages. Since then, the threats from ruling party sympathizers towards their family, who were always openly critical and demanded a change in the country, did not stop. Three years later, Sofia was also the victim of two police officers who intercepted, hooded and beat her, she said. Both were affected psychologically after these aggressions, so their parents decided to send them to the United States, where they had relatives.

The sisters left Leon on August 1 at 11:00 p.m. for Managua, from where they departed in a private vehicle from a company providing overland travel in the region. When they arrived in Guatemala, a car took them to a city near the Mexican border where they met with the “coyote”. They began a difficult journey in the company of 15 people, including Cubans, other Nicaraguans and a Honduran family whose youngest member was a three-month-old baby.

They crossed a river to Mexico and then always moved at dawn in several medium-sized vehicles in which they had to pile up. “In a caravan, very quickly, we travelled at that hour through dirt streets to avoid the police,” says Sofia. There were some parts of the trip in which they traveled with interstate public transportation in which, in case they were stopped by immigration or police authorities, they had to hand over money to be allowed to pass, says the young woman.

Sofia and her sister also felt the suffocating sensation of traveling hidden in a bus with bags and suitcases on top of them for eleven hours until they arrived in Ciudad Acuña. Sofia had to carry a six-year-old girl across the Rio Grande and then walk into U.S. territory until she encountered border patrols on August 15, after two weeks of travel.

The migrants with whom Sofia and Camila traveled during the crossing of the Rio Grande between Mexico and the United States. Photo: Courtesy

That day the sisters had to separate and have not seen each other since. Sofia, then 17, was transferred to a shelter for minors and was later able to go to Virginia to live with an aunt; while Camila, 18, was detained for a month in a center for adult migrants and then left for Miami, where another aunt was staying. Both are waiting for the resolution of their asylum petitions and to be reunited.

Sofia is dealing with the pain of not knowing when she will see her parents again. She also suffers for all that she planned and could not be. “My dream was to be a physiotherapist but my life changed, my expectations to study, to prepare myself. I did not think I was going to leave the country like this and come to make a life here. I didn't want to be in Nicaragua anymore, I didn't want to go through anything else,” she says. Like her, other young people her age have also recently emigrated to the United States: a friend of hers traveled in a group of 200 people who were detained by the police in Mexico, and during her time at the shelter for adolescents and children, she even coincided with a schoolmate, whose parents had also preferred to have leave the country.

Before emigrating, Meyling Cruz, a 22-year-old from La Trinidad, Estelí, was in her final year of her degree in Social Communication and although she worked in customer service at a finance company, she was mainly financially dependent on the remittances that her mother and father sent from the United States, a country where they had gone many years ago in search of work.

After the outbreak of the crisis in 2018, Meyling, who had participated in some protests and had received threats from Sandinista sympathizers for that reason, saw how the situation in Nicaragua only tended to worsen, so she decided it would be better to join her parents in the northern country. She got a “contract”, paid $4500 and left with her 26-year-old sister and 58 other Nicaraguans, almost all from La Trinidad, in the early morning hours of July 2.

The group traveled regularly on an “excursion” from Managua to Guatemala, then toured Mexico irregularly, but always in a tourist bus. However, the “organizers” provided false Mexican IDs and gave instructions not to speak, so that the authorities would not recognize the foreign accents of the travelers.

“It was very dangerous, we were scared the entire time”, she says, especially recalling a shootout between mafias in Sinaloa, when the group had to hide for several hours in the bush. “I was just shivering from fear and the cold, and I was praying the rosary as I went by thinking that that's as far as we were going to get”, she recalls.

“You feel more fear because you are a woman and young, some drivers and ‘organizers’ looked at us inappropriately”, she adds.

Finally, the group arrived in Altar, a city in Sonora, where they stayed for a week before crossing into the United States. Meyling says that the “coyotes” divided the group in two and handed them over to the U.S. authorities in sections. She and her sister arrived on July 20, after 18 days of crossing, and applied for asylum.

The part of the journey that marked her the most was her 52-day stay at the detention center in Tucson, Arizona, where she had to be separated from her sister, who had tested positive for covid-19, although fortunately she recovered and was released a few days later.

Meyling, on the other hand, had to post a $5,000 bond and pass a series of interviews. “There were many Nicaraguans in the same situation as me in that center, in my block alone there were 15 of us, but in the common yards I saw more,” she assures.

Emigrating under those conditions is not easy and even less so for those with depression, as in the case of Meyling, who was seen by a psychologist who, instead of helping her, made her feel very bad. “She told me that I was a criminal, that they were not going to let me in, that I was only coming to take advantage of the U.S. government,” she says.

She was finally reunited with her family in Los Angeles. The meeting was emotional, because she saw her father in person for the first time, since he had emigrated to the United States when Meyling was a baby. The trip had been worth it. “Nicaragua gives me a lot of sadness. I was going to finish my degree, and then what was going to become of me? With a salary that is not enough to make ends meet, one feels helpless. There is no hope,” she explains.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense desde 2007, con experiencia en prensa escrita, televisión y medios digitales. Tiene una especialización en producción audiovisual y una maestría en Medios de Comunicación, Estudios de Paz y Conflicto de la Universidad para la Paz de las Naciones Unidas. Fundadora y editora de Nicas Migrantes, proyecto por el cual ganó el Impact Award 2022 del Departamento de Estado de EE. UU. Ha realizado coberturas in situ en Los Ángeles (Estados Unidos), México, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua y Costa Rica. También ha colaborado con France 24, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, BBC World Service. Ha sido finalista y ganadora de varios premios nacionales e internacionales, entre ellos el Premio Latinoamericano de Periodismo de Investigación Javier Valdez, del Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS), 2022.

PUBLICIDAD 3D