25 de mayo 2016

Dialogue and Elections: “The Peaceful Way Out of the Dictatorship”

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

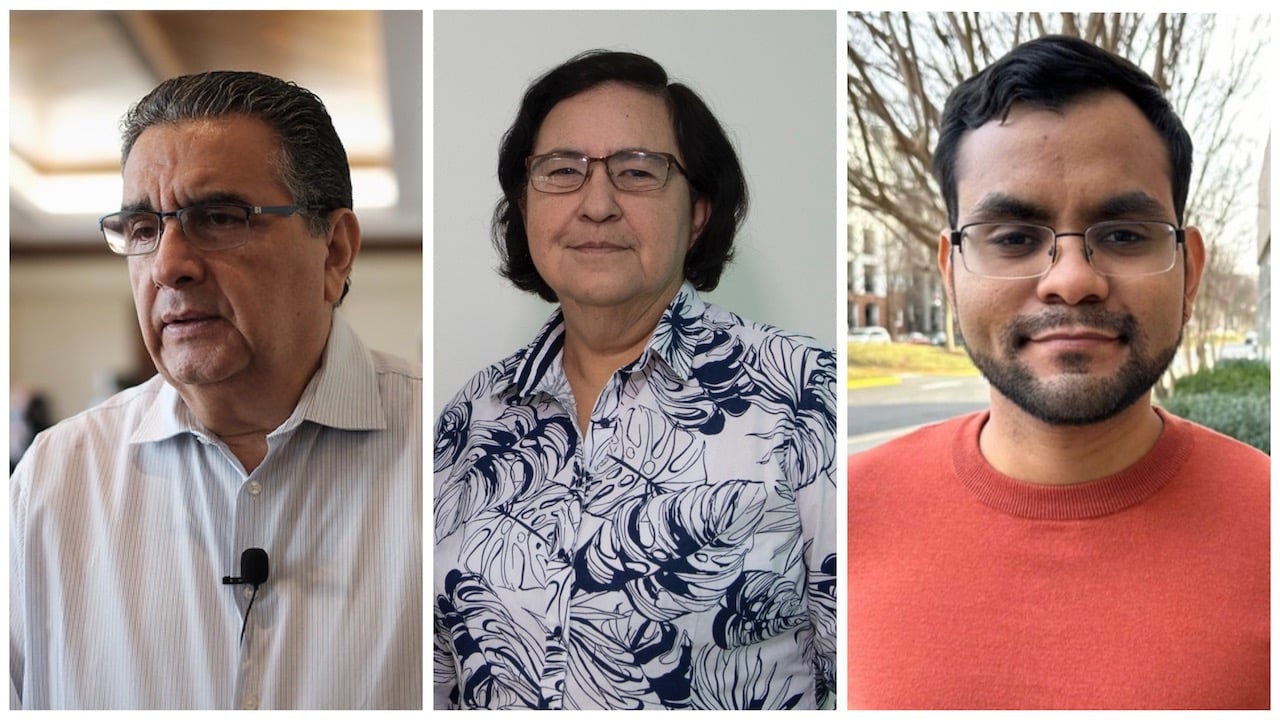

With over 40 years of medical practice in the United States, he founded and presides over the largest and most prestigious group of kidney specialists

The doctor Camilo Barcenas and his family. Photo: Courtesy.

This Nicaraguan, born in Managua in 1944, moved to the U.S. at the end of the 60s. There he became a nephrologist and today is the head of “Renal Specialists of Houston”, a group of specialists that oversees the care of more than 1,500 dialysis patients and performs around 80 kidney transplants a year.

“I knew that surgery required extraordinary manual dexterity and I never had this, so I preferred to apply myself more to the diagnosis and resolution of problems in internal medicine,” he explains.

For this reason, and as his small revenge, he studied what was to him the most complicated internal medicine specialty of the era: Nephrology. Following his studies in Dallas, Texas, he planned to return to Nicaragua with his diploma. The government - then under the rule of the Somoza family - that had blacklisted him and forced him into exile, would have to give him work. He would be only the second doctor in the country specialized in kidneys and kidney diseases and the Somozas would have no choice but to hire him. Or, at least, so he believed.

It had all begun in Leon in 1960, during his time as a university student. Barcenas arrived at the Autonomous Nicaraguan National University (UNAN) just one year after the July student massacre perpetrated by Somoza’s National Guard and found himself tangled up in the student struggles.

The UNAN was “politicized” and he couldn’t remain on the fringes. He promoted strikes. He got involved with opponents of the regime. Soon his name was added to the blacklists. According to him, it was Hope Portocarrero – Anastasio Somoza’s wife, first lady and president of the National Board for Social Aid and Assistance – who put him on the famous lists. There would be no job for him, then or ever.

“They wouldn’t let me work as a resident, nor as an aide, nor in the Social Security, nor in the public hospitals. Nowhere,” Barcenas recalls.

He was forced to leave. He had planned his triumphant return and was ready to turn it into reality when the Sandinista Revolution erupted.

The first kidney transplant

The last time that Camilo Barcenas attempted to count the patients he had attended was at the beginning of the 90s. By then he estimated that he had treated nearly 3,000 cases of severe kidney disease.

After graduating from the University of Texas, Barcenas trained at Parkland Memorial Hospital – famous in the United States because President John F. Kennedy was taken there in 1963 after he was shot. Later, he was put in charge of the dialysis unit at the Veterans’ Hospital, and was selected to set up the nephrology unit at St. Luke’s Patient’s Medical Center in Houston.

In 1977 he moved to that city, one of the country’s most populous, with his family. They thought they’d only be staying there for a few years; it was closer to Nicaragua, and they could wait there for the upheaval in the center of America to calm down. But when the Sandinista Revolution arrived, the decision went from temporary to definitive and Dr. Barcenas resolved to make the United States his permanent home.

That’s when he recruited his first partner and formed “Renal Specialists of Houston.” According to his website, it’s the largest nephrology practice in Houston and one of the ten largest nephology centers in the United States, with 22 kidney specialists who provide complete attention to the patients, from admissions to treatment, infection control and renal transplants.

The first time Dr. Barcenas participated in a transplant procedure of this type was in 1982. A young man of 22 would be donating a kidney to his father. Barcenas prepared the patient to receive the transplant and provided follow-up care after the operation to keep his body from rejecting the new kidney. The operation was a success.

A few years later, the young donor died in an auto accident. His father is still alive. “He still has his son’s kidney, he still comes in for dialysis,” the Nicaraguan doctor noted.

Today, Bárcenas sees very few patients and dedicates his time to administrative functions. He oversees the practice’s good standing and assures that the cases they accept receive the right attention.

Rabbits and singers

Camilo Barcenas was raised between Managua’s Candelaria neighborhood and the family farm in Tipitapa. During the nights at the farm when they hunted, he developed an interest in biology.

He would take the rabbits they’d trapped for dinner, open their bellies and examine their anatomy. He liked to note where their organs were. He always knew that he wanted to be a doctor.

His first years of school were spent in the Colegio Calasanz that collapsed in the 1972 earthquake. There he became friends with musician Carlos Mejía Godoy.

Upon graduating from high school he went to Leon to attend the university there. He was the best internal medicine student in his class.

He did his internship in the now defunct El Retiro Hospital, where he became interested in the area of nephrology; in fact, he was one of the first people in Nicaragua to use dialysis.

A Columbian singer named César Andrade was his first patient. He’d been poisoned during a night of partying and his kidneys were paralyzed. With dialysis – even in the rudimentary form that existed in 1966 – they succeeded in eliminating the excess toxins from his blood.

The Columbian survived, and afterwards, whenever the doctor would attend his performances at the Country Club or the Terraza Club, he’d stop the music and announce: “Here’s Dr. Barcenas coming in. He saved my life.”

Becoming a doctor in the US

From the time that Camilo Barcenas arrived in the U.S. until now, the advances in nephrology have been “astonishing” he assures us.

During the 60s there were fewer than a thousand people undergoing dialysis in that country; by 1972 the number had risen to 10 thousand. All this was because of a law that ordered the government to assume the cost of the treatments that would run between 25 and 35 thousand dollars a year for each patient. In contrast, Nicaragua’s law #847 for Human Organ, Tissue and Cell Donation and Transplant is still lacking the legal norms and regulations. In addition, there’s no central list of the country’s donors or of patients in urgent need of a kidney.

Transplants of these organs are very successful, Bárcenas underlines. A person that obtains a kidney from a live donor can live for 25 - 30 years with it. One from a deceased donor can last 15 - 20 years.

There’s one patient that this nephrologist will never forget. John Moore Washington was a 50 year old janitor who survived kidney failure, more than three years of dialysis, and the transplant surgery. His body accepted the new kidney, but a month later he died from a case of chicken pox that he caught from his grandson. This all happened because at that moment there were no medications to save him.

“Incredible, no? And frustrating as well,” the doctor laments.

And Nicaragua?

Barcenas with his white hair, black eyebrows and chiseled lips, considers his family to be his greatest achievement. He’s been married for more than 40 years to Aurora Cárdenas, also Nicaraguan, and is father of three children and grandfather to five.

Lover of the Bossa Nova, the opera and science fiction movies (the Hunger Games series figures among his all-time favorite movies), this doctor visits Nicaragua 3-4 times a year. He comes to visit his friends and family.

He’s always been involved with his country. In the middle of the contra war he received young graduates in medicine who were fleeing Nicaragua and helped them train in the United States. Over a twenty-year period, he assisted 20 of them, helping them to obtain work or to enter training and English language programs.

At 72, Barcenas doesn’t hunt any more. He hasn’t aimed a rifle since entering medical school, and despite the fact that his first steps as a doctor were with the knife, nearly 60 years have passed from his days of dissecting rabbits, and he has achieved fame in other areas. It’s all thanks to his “manual incompetence” he says laughing, to his two left hands.

This article has been translated from Spanish by Havana Times.

Read the original version here.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D